Sex Workers' Rights - What & Why?

I'm working on a long-term project about sex workers' rights. Fundamental concerns for sex workers include access to health, social services and protection under the law – free from stigma and discrimination. I use writing, photography and video, in collaboration with individuals and the organisations representing them, to amplify their voices.

Since the project began in 2013, I've worked closely with the New Zealand Prostitutes' Collective, as New Zealand is one of the few countries in the world where prostitution is decriminalised and neither sex workers nor their clients are criminalised.

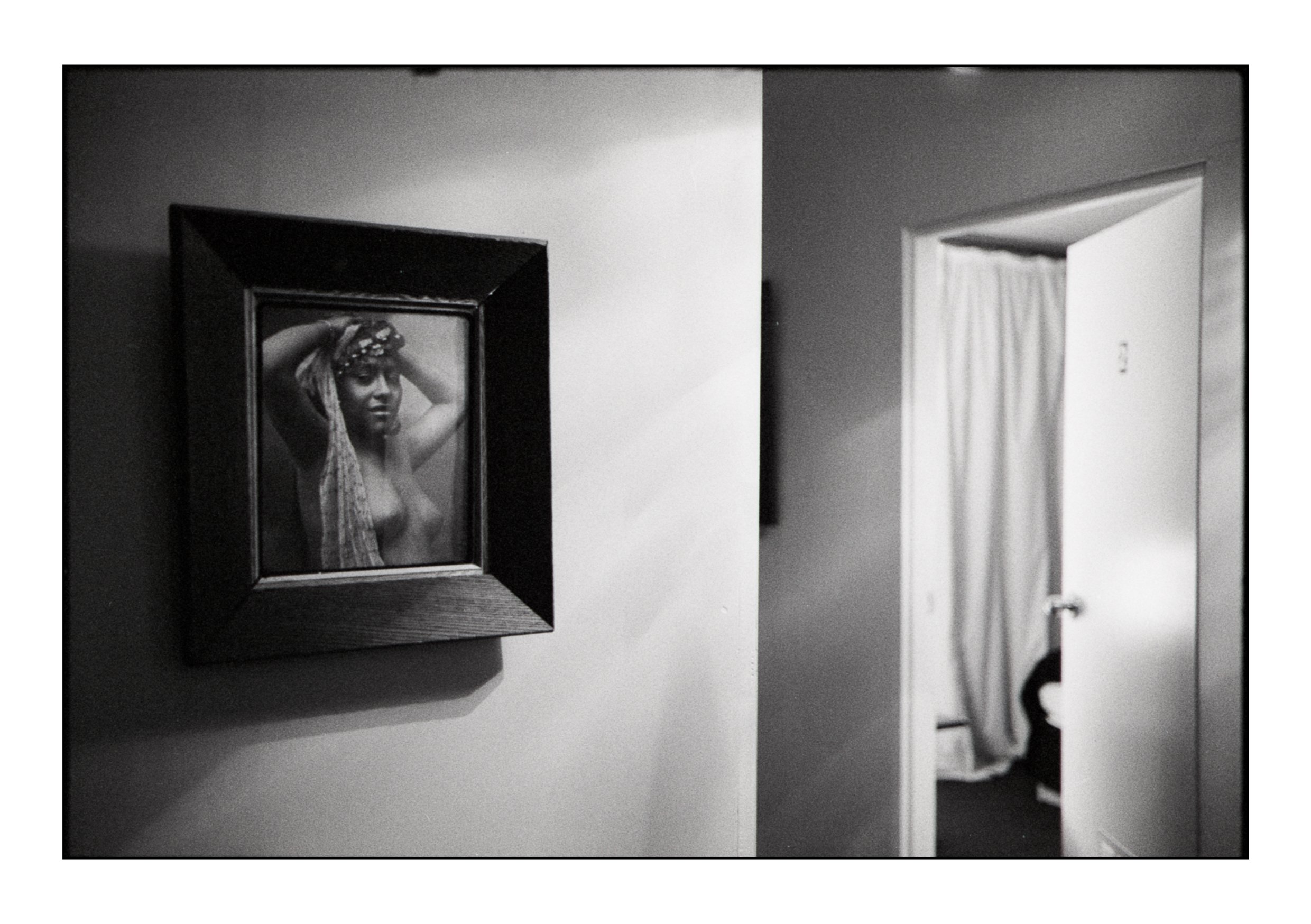

Interior: Paris, Lower Hutt, New Zealand *

Why?

I initially chose this topic for a number of reasons. Some were naive, but some have contributed to a mature and considered documentary approach. Here's some background about my motivation for starting this project.

Feminism and White Ribbon

In 2009, while I was living in Edinburgh, a friend invited me to join a White Ribbon Scotland group. White Ribbon is an organisation that aims to raise awareness and educate men about violence against women. Many of White Ribbon's values confronting men’s violence – domestic violence, assault, rape – I still think are important. During the six months I attended, a number of people from organisations including Zero Tolerance, Rape Crisis Glasgow, and Shakti Women’s Aid came to talk to the group about men's violence against women. Violence against women – and specifically what contributes to and causes it – was presented in black and white, as cause and effect. In discussions of the sex industry, men's power relations over women were seen as being reinforced through objectification, which enabled violence and reinforced women’s inequality. White Ribbon had run sticker campaigns against lads' mags and they had picketed lap-dancing clubs in Glasgow (with no consideration of the financial impact on the workers), and they were very, very loud on the subject of sex work and specifically the criminalisation of sex workers’ clients.

Much of the time we focused on analysing a particular stream of radical feminist ideology rather than providing financial support or contributing to any of the organisations involved. I found the oversimplification of the causes of violence frustrating and thought it naive that simply by signing a pledge we could somehow 'magic' men’s violence against women away. I found it incredibly unrealistic in its expectations and engagement with men in Scotland – Glasgow at that time having the highest murder rate in Europe.

The last night I attended White Ribbon, Ruth Morgan Thomas from the sex workers' collective SCOT-PEP spoke to the group. At that time I had no real knowledge about sex work and I had no strong opinion on the Swedish/Nordic model which criminalises the clients of sex workers.

Ruth spoke about the Swedish model but she spoke more generally about White Ribbon and organisations like Zero Tolerance and their engagement (or lack thereof) with the communities Ruth represented. Ruth was particularly articulate and genuinely angry about three things. She said that they treated sex workers like victims, that no one listened to sex workers when they said they did not want criminalisation of their clients or themselves, and that when many feminists did listen to them they patronised them – because how, after all, could such damaged victims possibly speak for, represent or organise for themselves? There were many reasons to drop out from White Ribbon, but even to this day I can still hear Ruth sitting in a crappy Edinburgh pub trying to make people see that sex workers are just people, not a fucking label.

I'd love to say this experience made me connect with sex workers’ rights activists and take action, but it didn’t – or at least, not immediately.

Writing and Photography

I have a guilty secret that I’m embarrassed to share because of the apparent disconnect with my current focus on documentary photography. When I first wrote and photographed for publication in 2010 I wrote about rock climbing, the outdoors and the environment. Although on the face of it, that has no connection whatsoever with the topics I now work on, I learned a great deal from writing for New Zealand’s Wilderness magazine. I will always be immensely grateful to Alistair Hall, the editor of Wilderness, for the opportunity he gave me to grow as a writer and photographer.

As my interest in photography matured I became more interested in photojournalism and rights-based issues. Around that time I took a language course and made friends with a classmate who worked as an escort. Not many people are open about working in the sex industry and certainly few are willing to endure many hours of me asking uninformed and naive questions – but she was. Through that, I became interested in trying to work on something (I really didn't know what at the time) about sex work.

Photography?

If you look at the imagery related to sex work – photojournalists and fine art photographers, newspaper and magazine coverage, campaigns against sex trafficking – it tends to be highly emotive. As a subject that people respond to and have strong opinions about, sex work is one area that photographers and journalists return to again and again. In that, I am no different.

The media stereotypes sex workers, using a series of tropes to ‘other’ them. For instance: drug use and abusive family backgrounds are drivers for people to participate in the sex industry; the sex industry is exploitative; pimps dupe, traffic and exploit women and girls (all sex workers are women). Then there’s the Pretty Woman narrative; the (white) call-girl student trying to temporarily make some extra cash, mainly for our salacious media interest; and the Third World women needing Western assistance to rescue them from prostitution. The imagery somehow remains sexualised: stilettos, fishnets and body parts, no matter what the angle.

Diverse kinds of people work in the sex industry. There are male and female sex workers; cis and trans sex workers. There are people who work in porn, as escorts, in a parlour or on the street. Single and married sex workers. Some are parents and caregivers. Some people choose to work, some are financially driven to work. There is no ‘generic’ sex worker who is desperate to exit the sex industry.

“Shaming and stigma silence people. Shame means you are afraid to talk. Stigma means no one will listen to you if you do.”

But to simply deny the stereotypes is a mistake. There are people who are exploited, people who have drug dependencies, people who are escaping abuse and entering sex work out of economic necessity. And that is exactly why people need access to the same human rights free of discrimination. Those fundamental human rights are what attract me to this topic.

We stereotype people we don't know and don't understand – particularly when we are frightened of what they represent – and we exclude them. The principal way society excludes sex workers is through shaming – shaming and stigma. Shaming and stigma silence people. Shame means you are afraid to talk. Stigma means no one will listen to you if you do.

The problem with othering people in the way that stereotypes do is that it says these people are not like you. I think the media contributes to that. If you look a bit deeper at some of the photographers and documentary makers behind the stereotypes, you’ll find that many of them get access to their subjects through law enforcement agencies or NGOs attempting to ‘save’ sex workers, while in some cases they pretend to be someone they are not and dupe people into being captured on camera. They don't do any research and more importantly don't talk to sex workers or try to understand how they wish to be represented. The media seems to have a lot to say about sex work, but doesn’t seem to be so interested in listening to sex workers.

I always find it difficult when pressured to answer ‘Why?’ I'm not very good at explaining unless it's on paper. When I was in New Zealand last, a sex worker friend was talking about why they are an activist within their community. They said it went back to their childhood and some of the crappier things that happened then. They said that ever since then they had a sense that some things were not fair when they should be, and it felt good to stand up and not just sit there and take it. I recognise the same in me, so if you are looking for a simple 'why?' then it goes rather deeply and perhaps that's why sometimes it can be difficult to say.

But why would we work with yet another outsider?

Because outsiders bring skills, perspectives and ideas that a community may not have access to or resources to fund. Outsiders can act as bridges to other communities. I say this having talked with many people since 2013 who are or were sex workers and who have achieved a great deal for their own communities. I'm very aware of the suspicion and concern people have about non-sex workers writing about, filming and photographing them, and I've had to answer very pointed questions and felt what it's like when people still openly do not trust you even after you have answered all their questions as best you can. It's not a particularly easy journey, but when you remember the stigma faced by sex workers and how poorly served they are by traditional media, it's easier to understand. I now also have experience of working with NZPC over the last few years and I know that Catherine, Calum, Ahi, Chanel and Annah don't suffer fools. Outsiders can be useful, and if you want an example of an outsider who works with a community, have a look at the section on Photography Process and Robin Hammond's project Where Love Is Illegal. I'm only at the beginning of this project and still have much more to learn and to contribute.

Very long and very dull ... so what the hell do we get out of it?

I was talking with someone recently who said that they didn’t really think 'awareness raising’ through writing does much. I agree. I don’t think a photograph or a piece of writing changes people's lives very much at all. I think outreach does. I think a change in legislation does.

Writing and photography don't change people's lives in a practical way. And I don't believe in that hokum about my voice giving voice to the voiceless. Juno Mac's eloquent and impassioned TED Talk is just one example of the articulate activism that's part of the sex work community.

In her talk she uses this quote:

“There’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless’. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.”

— Arundhati Roy

Some of the worst writing and photography comes from those who smugly believe they are giving 'voice to the voiceless' whilst directly contributing to silencing the community they document. I am not working to do that.

Communities don't exist in isolation. They do need people to share their stories, to collaborate and – in an increasingly digitally rich world – augment stories. Not everyone can write, not everyone knows what makes a good photo, not everyone can edit video: I, to a lesser or greater degree, can do these things.

* A note on the image from Paris - a picture of a picture of a half-naked woman? Stigma and stereotypes keep sex workers hanging in frames just like this.

Notes:

If you are interested in seeing how the stereotypes around sex worker imagery can be challenged have a look at the {Whore}tography Visual Activism project

Never Give a Cent to White Ribbon

Ten Reasons I Will Ignore White Ribbon

Sex Worker Open University: A Note to Researchers